“The worst day under our Treaty Agreement was better than the best day under the Indian Act.” – Joe Gosnell, Nisga’a Senior Negotiator

For generations, Williams Lake First Nation has lived under the restrictions of the Indian Act — a colonial system that limits our ability to make decisions for our people, our lands, and our future. Self-government is about changing that. A Self-Government Agreement empowers WLFN members to live by our own laws, manage our own lands and membership, and take back decision-making power over areas like education, health, children and families, and community services. We govern ourselves outside of the Indian Act, in ways that reflect our laws, traditions, and values. Authority shifts from federal control to community control, with us deciding how our leaders are chosen under our own constitution. The government becomes accountable, ensuring transparency through community engagement before making high-level decisions. WLFN members, including those living abroad and future generations, are included in government processes. While self-government brings greater freedom, it also demands strong leadership accountability and gives members the right to question and challenge decisions.

These processes do not create new rights — they reaffirm the inherent rights and title we have always held and never surrendered. Through self-government, we can build a more self-sufficient and self-determined community, strengthen our culture, protect our lands and resources, and create new opportunities for generations to come. It is about moving beyond the Indian Act and establishing a true government-to-government relationship with Canada and BC, based on respect, recognition, and reconciliation. “Under our Agreement, any decisions made for us will be made by us.” – Joe Gosnell, Nisga’a Senior Negotiator

History

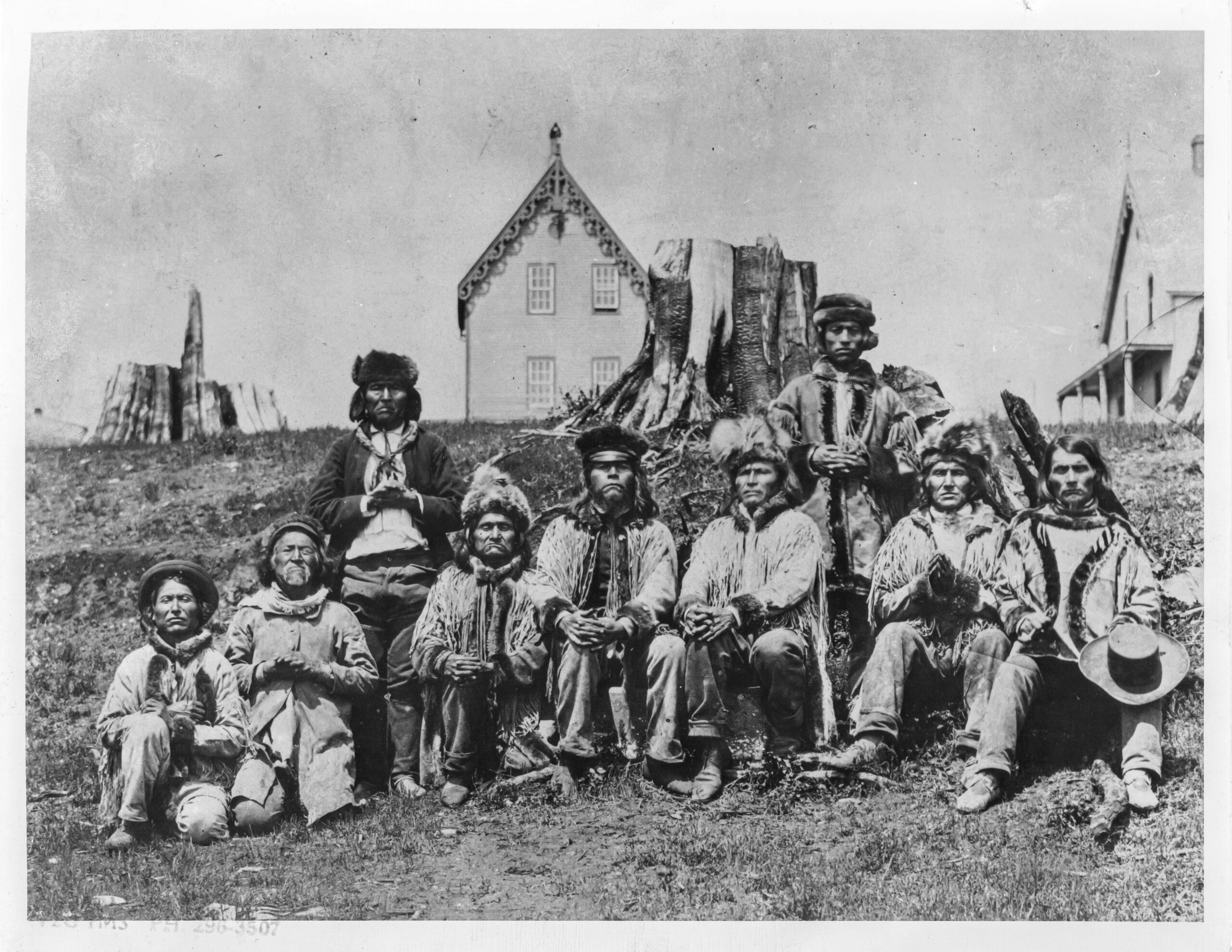

The Secwépemc have occupied Secwépemcúĺecw since time immemorial, with a vast territory covering 180,000 square kilometers in central and southern BC. Williams Lake First Nation is one of 17 Secwépemc communities that make up the Secwépemc Nation. Originally, there were 32 Secwépemc communities, but the 1862–63 smallpox epidemic wiped out two-thirds of our population, reducing the number of communities to 17. Today, the Secwépemc Nation has approximately 10,000 members; had the smallpox epidemic not occurred, our population could have been closer to 30,000.

Prior to European contact, the Secwépemc maintained complex political, social, economic, and governance systems. Despite the vastness of our territory, these structures allowed us to manage and protect our lands sustainably, ensuring resources for generations. Archaeological evidence and oral histories show that we have occupied these lands for over 10,000 years, with evidence including village sites, pithouses (kekuli), trails, cultural sites, place names, and landforms.

Our oral traditions tell us that Secwépemcúĺecw was a sacred trust, handed to us by the Creator to hold and manage for future generations. Our lands were never seen as commodities to trade or sell; instead, we were taught to view the land as a relative, deserving respect and stewardship. This worldview emphasizes sacred relationships with the land, waters, and all living beings, and forms the foundation of our governance and resource management practices.

The Secwépemc worldview regarding land and resources has historically conflicted with European concepts of ownership and exploitation, leading to ongoing tensions during colonization. Despite these challenges, the Secwépemc continue to reaffirm our inherent rights, cultural responsibilities, and jurisdiction over our unceded territory.

Territory

Secwépemc territory extends:

- North: near McBride and the Cariboo Mountains

- South: to the Arrow Lakes and areas near Revelstoke

- East: into the Rocky Mountain Trench

- West: toward the Fraser Canyon and Chilcotin Plateau, including Hanceville

Way of Life and Stewardship

The Secwépemc followed a seasonal round, moving through their territory to harvest fish (especially salmon), hunt and trap game, and gather plants, berries, and medicines. Large winter villages, made up of semi-subterranean pithouses (kekuli), were primarily situated along rivers and lakes, while warmer months were spent traveling to resource sites. Extensive trails, trade networks, and kinship ties connected Secwépemc communities with neighbouring Nations, including the Nlaka’pamux, St’át’imc, Syilx, Tsilhqot’in, and Ktunaxa.

The 1800s and early 1900s marked a dramatic shift in the lives of the Secwépemc people. During this period, the Canadian government introduced the Indian Act (1876) and implemented the reserve system, confining Indigenous communities to small parcels of land and restricting their traditional ways of life. Lands were pre-empted by settlers under colonial policies, often without consent or compensation, disrupting the Secwépemc’s long-established patterns of hunting, fishing, and gathering. These changes undermined the authority of Secwépemc Chiefs and imposed foreign laws that conflicted with traditional governance and social structures. It was against this backdrop of dispossession and legal control that the Williams Lake First Nation’s leaders began advocating publicly for recognition of their rights and the protection of their territory.

In 1879, Chief William submitted a grievance letter to the Victoria Colonist to voice his discontent over the loss of his lands and authority over his people (read the whole letter here).

The second Chief William continued this fight for the Title and Rights of the Williams Lake First Nation when, in 1910, he joined the Secwépemc Nation’s Chiefs in signing the Memorial to Sir Wilfrid Laurier (read the whole letter right here). In the memorial, the Chiefs stated that they were once supreme in their territory:

“They found the people of each tribe supreme in their own territory and having tribal boundaries known and recognized by all. The country of each tribe was just the same as a very large farm or ranch belonging to all the people of the tribe) from which they gathered their food and clothing etc…, and all necessaries of life were obtained in abundance from the lands of each tribe and all the people had equal rights to access everything they required.”

However, as the settlers grew more powerful, the relationship between them and the Secwépemc worsened. The Chiefs complained that:

“they treat as subjects without any agreement to that effect and force their laws on us without our consent, and irrespective of whether they are good for us or not. They say they have authority over us. They have broken down our old laws and customs (no matter how good) by which we regulated ourselves.”

In their final statement, the Secwépemc Chiefs demanded that the land question be settled:

“We demand that our land question be settled and ask that treaties be made between the government and each of our tribes, in the same manner as accomplished with the Indian Tribes of the other provinces of Canada and in the neighbouring parts of the United States. We desire that every matter of importance to each tribe be subject of treaty, so we may have a definite understanding with the government on all questions of moment between us and them.”

This memorial was significant because it was one of the earliest unified political statements by BC First Nations to Canada, clearly stating that their inherent rights and ownership of the land must be respected.

T’exelc (WLFN) entered negotiations regarding inherent rights and title with BC and Canada in December 1993, along with the other Northern Secwepemc Communities who make up the NStQ or Northern Secwepemc te Qelmucw. NStQ members First Nations are:

• T’exelc (Williams Lake First Nation)

• Xatśūll Cmetem’ (Soda Creek/Deep Creek

• Stswēceḿc Xgāt’tem (Canoe Creek/Dog Creek)

• Tsq’ēsceń (Canim Lake)

The NStQ has been negotiating with BC and Canada ever since. The process is slow and frustrating. There have been many setbacks. However, progress is being made. Negotiations are now at Stage Five of a six-stage process. The goal is to ensure Secwépmec laws, inherent rights and title, and sacred duty to protect Secwépemcul’ecw (people, land, and culture) are permanently upheld and respected in Canadian and international law.

“Our members don’t understand that our laws have never been lost or given up. They were replaced with someone else’s laws. We just have to bring back our own laws and start using them again”.

— WLFN Elder

The Self-Government Department’s goal is to reflect WLFN members’ wishes. They told us to bring them a potential agreement protecting the wisdom of Elders, enabling the aspirations of youth, and recognizing our duty to sustain the health of ancestral lands given to us by the Creator. Along the way, they expect consultation and discussion regarding choices to be made.

In the future, all eligible WLFN members will vote on a proposed agreement. Alongside their Elders and parents, today’s WLFN youth will help choose the path forward. Discussing the topics in community, with family and friends, young and old is essential. Understanding the benefits, responsibilities, and trade-offs will help the citizens of T’exelc make their choice in a good way.

On June 22, 2012, the 17 Secwepemc Chiefs signed the Secwepemc Unity Declaration declaring that the 17 Secwepemc Communities would stand together as one Nation. The Secwepemc Declaration states that we:

- Will be one united people – Even though there are many Secwepemc communities, they declared they are all part of one Nation with shared rights, responsibilities, and territory.

- Will Protect the land – They affirmed their duty to protect Secwepemc lands, waters, and resources for future generations, based on their own laws and traditions.

- Have Inherent rights – They reminded governments and industry that Secwepemc rights and title come from their ancestors and have never been given up or extinguished.

- Will make decisions together – They committed to working together as a Nation when it comes to major decisions about their land, rather than being divided community by community.

- Will respect for their laws – They emphasized that Secwepemc law and governance are still alive and guide how they care for their people and territory.

The declaration states “We are one people, we never gave up our land or rights, and we will stand together to protect our territory according to our own laws.”

Current Negotiations Status

Williams Lake First Nation is presently in Stage Five of a six-stage treaty process.

Stage One: Statement of Intent

A First Nation wanting to initiate treaty negotiations must file a statement of intent with the Treaty Commission. The statement must: identify the First Nation and its members; describe the First Nation’s traditional territory; indicate that the First Nation has a mandate to enter into and represent its members in treaty negotiations; and appoint a formal contact person.

Stage Two: Preparation for Negotiations

The three parties confirm their commitment to negotiate a treaty, establish that they have the authority and resources to commence negotiations, have a means of developing their mandates and broadly outline what each of them wishes to negotiate.

Stage Two: Readiness Documents

By the end of Stage Two, Canada and BC must also submit readiness documents to the Treaty Commission in which they identify community interests in the region and establish ways to address those interests. The table moves on to Stage Three when the Treaty Commission is satisfied that the parties have met these requirements.

Stage Three: Negotiation of a Framework Agreement

The Framework Agreement defines the issues the parties have agreed to negotiate, establishes the objectives of the negotiation, identifies the procedures that will be followed and sets out a timetable for negotiations. The parties expand their public consultation in local communities and initiate a program of public information.

Stage Four: Negotiation of an Agreement in Principle

Substantive negotiations take place in this stage. Land, resources, self-government and financial components usually form part of the negotiations. The Agreement in Principle sets out the key objectives and elements to be part of self-government.

Stage Five: Negotiation to Finalize a Self-Government Agreement

At this stage, outstanding legal and technical issues are resolved. Formal signing and ratification of the agreement brings the parties to Stage Six.

Stage Six: Self-Government Agreement Implementation

The plans to implement the self-government agreement are put into effect or phased in as agreed. The table remains active to oversee the implementation of the agreement.

Many First Nations in Canada are currently negotiating with provincial and federal governments to recognize the inherent rights and title that have been suppressed since colonization. Each negotiation is unique. Two approaches, treaty or self-government agreement (SGA), are the most common frameworks. Each model has advantages and disadvantages.

What is a treaty?

A treaty is a formal agreement between a First Nation, Canada, and usually the province. It sets out long-term arrangements across the whole traditional territory, covering land, resources, governance, and rights. Treaties are broad in scope, constitutionally protected, and often take decades to complete. They can also require compromises that limit flexibility.

What is a self-government agreement?

A self-government agreement, by contrast, is more focused. It applies to our reserve lands and recognizes our inherent right to govern our own affairs such as education, health, culture, language, and community decision-making, without requiring us to settle land and resource issues at the same time. This path allows us to move forward more quickly and begin exercising greater authority over the areas that matter most to our people today.

How are they different?

Both paths are important and work best in parallel: self-government gives us practical control over our daily governance, while treaty negotiations remain the avenue for addressing rights and interests throughout our full traditional territory. To achieve both, we need Canada at the table (with jurisdiction over governance) and BC as well (with jurisdiction over lands and resources).

Treaty agreements are designed to empower our peoples to govern our political, economic, social, and cultural affairs, fostering autonomy and cultural integrity within a recognized legal framework. When formalized through treaty agreements, it provides legal certainty, stable funding, and long-term economic partnerships. These treaties strengthen financial stability through predictable revenue-sharing, improved access to capital, and reduced administrative costs. They also drive sustainable economic growth, job creation, and land stewardship—benefiting both our communities and the broader Canadian economy through shared prosperity and social well-being. Read more about treaty and self-determination here (click link).

Canada’s Constitution outlines two main levels of government: federal and provincial. The federal government handles national issues like defense and trade, while provincial governments manage regional matters such as education and health. Local governments exist but derive their authority from the provinces, lacking constitutional status. The term “Third Order of Government” describes Indigenous governments also seen as a distinct level of government with rights independent of federal and provincial control. While this status is not yet formally recognized in the Constitution, it is supported by Section 35 of the Constitution Act and Supreme Court rulings affirming Indigenous self-governance. The Government of Canada accepts that Indigenous nations have an inherent right to self-government, a right that predates Canada itself. Additionally, numerous Indigenous nations have entered into modern treaties and self-government agreements, acknowledging their authority to govern and legislate over certain areas typically managed by provinces.

Indigenous governments in Canada function as a distinct and autonomous third order of government, not subordinate to provinces or municipalities. Their authority is grounded in inherent rights, treaties, nationhood, and constitutional protection. They have the power to create laws related to various areas such as education, health, culture, and land management, reflecting their self-governance. The relationship between Indigenous nations and the Canadian government is framed as nation-to-nation and government-to-government, recognizing their equal status in governance. While the federal government has jurisdiction over Indigenous matters, it is increasingly viewed as part of a collaborative relationship rather than a controlling one. Furthermore, provinces must respect Indigenous rights and collaborate on issues like land and education. Although not explicitly defined in the constitution, the recognition of Indigenous sovereignty is growing, supported by court rulings and modern treaties. Acknowledging Indigenous self-government benefits communities through improved services, accountability, and cultural continuity, showcasing an evolving governance structure in Canada.

In our negotiations with Canada and British Columbia, we bring powerful tools that affirm and protect our rights. These tools ensure that our voice is strong at the table and that the process reflects both Canadian law and Secwépemc law, as well as international standards of justice.

Case law

Over decades, Indigenous Peoples have brought forward landmark legal challenges that continue to shape the Canadian legal landscape. Court decisions such as Calder, Delgamuukw, and Tsilhqot’in confirm the existence of Aboriginal Title and Rights and affirm that these rights must be recognized and respected by governments. Caselaw provides powerful legal precedent that supports our inherent right to self-government and strengthens our position at the negotiating table. Read about some of the seminal cases that support us in our negotiations with Canada and BC here (click to access).

UNDRIP

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) sets an international standard for the recognition and protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Canada and BC have both committed to implementing UNDRIP, which means they are obligated to align their laws and policies with its principles. This includes free, prior, and informed consent, and recognition of our rights to lands, resources, culture, and self-determination.

Section 35

Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes and affirms “the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.” This section provides a constitutional safeguard for our inherent rights and serves as a legal foundation for self-government. Negotiations must be consistent with Section 35, ensuring that our rights are not diminished or ignored. When section 35 was added to the Canadian Constitution in 1982, recognizing and affirming “the existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada,” there were no Modern Treaties in British Columbia, and there was little clarity on what rights were encompassed in section 35. This led to the creation of the BC Treaty process and the BC Treaty Commission in 1992.

Secwépemc Laws

Long before contact, the Secwépemc had well-established systems of law and governance that guided how we lived, managed resources, and cared for one another. These traditional laws reflect our values, governance structures, responsibilities, and deep connection to the land. They continue to guide us today, providing a cultural and spiritual foundation as we move toward a modern self-government framework. Secwépemc laws underscore the inherent rights and sovereignty of the Secwépemc people over their traditional lands and resources. These laws provide a framework for understanding the relationship between the Secwépemc Nation, our lands, and people. It also will establish the relationship between us and Canada and the province. By acknowledging Secwépemc laws in treaty negotiations, there is a recognition of the right to self-determination and self-governance. This includes the ability of the Secwépemc Nation to make decisions about its own affairs, including land use, resource management, and cultural preservation.

Recognition and Reconciliation of Indigenous Rights Policy

The Recognition and Reconciliation of Indigenous Rights Policy (RRR Policy; click here to read) is a commitment by Canada and BC to change how it deals with Aboriginal Inherent Rights and Title in treaty negotiations. The RRR Policy was negotiated by Canada, BC, and the First Nations Leadership Council of BC adopted and sign by the three parties on September 19, 2019. This was a major shift in how Canada and BC treated Aboriginal Title and Rights to that point. The previous policy, called the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy (CLCP), mandated the extinguishment or modification of Aboriginal Tile and Rights when signing a treaty or Self Government agreement. Another goal of the CLCP was to protect the interests of government and industry, without consideration for the Inherent Rights of First Nations. The new RRR Policy makes it clear that extinguishment and modification is no longer acceptable. In short, this policy is about moving from denial and control to recognition and partnership, so Indigenous Nations can exercise their Inherent Rights and make decisions for their people and lands.

Negotiations are a long, careful process involving Canada, BC, and our own Nation. Each side brings a Chief Negotiator, and we work within a framework that was established in Stage 3 of the treaty process to guide how negotiations unfold.

Every topic begins with the community. Before anything is discussed at the negotiation table, we hold meetings with our members to gather direction. When we sit down with the Chief Negotiators — often joined by ministry representatives, consultants, and lawyers — we carry forward the views and instructions of our people. If we hit sticking points, those get brought back to the community for input. If members say, “stand firm,” we do. If they recommend flexibility, we negotiate with that guidance in mind. At every step, the process is driven by community voices.

We move through subjects chapter by chapter, often revisiting earlier discussions as new issues arise. Experts and consultants support us along the way to ensure our approach is informed and strategic. While many of our pre-contact laws provide important guidance, not all can be applied directly in today’s context. We approach negotiations with that balance in mind — knowing we may not achieve everything we want, but aiming for agreements that are fair, practical, and respectful of our inherent rights.

In addition to our own negotiations, we participate at the “Common Table” with other Nations in Stage 5. The Common Table was established in 2007 to help First Nations overcome slow progress in the BC Treaty Process. Over 60 Nations, including WLFN, came together to collectively negotiate key issues that individual tables were struggling to resolve. Supported by the First Nations Summit and other leadership bodies, the Common Table provides a united voice to engage Canada and BC, ensuring recognition and reconciliation of Aboriginal Rights and Title remain central. By negotiating together, Nations can strengthen their individual agreements and promote the timely conclusion of fair, viable treaties.

Over time, chapters of our agreement are drafted, refined, and endorsed, each one representing another step in the reconciliation process and in building the foundation for true self-government.

Why Treaty Negotiations?

Canada and BC are in treaty negotiations with BC First Nation to resolve unresolved Title and Rights claims, create legal certainty, support self-government, and advance reconciliation without relying on endless court battles, Following is an outline of why Canada and British Columbia are engaged in treaty negotiations with First Nations in BC. Read more about this subject here (click link).

The pursuit of self-government is guided by the goal of protecting and strengthening who we are as Secwépemc people. Our negotiations focus on building a future where our rights, culture, and traditions are fully respected, while creating the tools we need to govern ourselves and care for future generations. These priorities are not chosen behind closed doors — they reflect what our community has identified as most important through an ongoing cycle of dialogue and engagement with our membership. The NSTQ treaty negotiation framework includes 32 chapters, covering these topics:

Definitions • General Provisions • Lands • Land Title • Subsurface Resources • Access • Crown Corridors and Roads • Co-management • Water • Forest Resources • Range • Fish • Gathering • Wildlife • Migratory Birds • Governance • Local Government Relations • Child and Family Wellness • Education • Health • Justice • Transitions • Capital Transfer and Resource Revenue Sharing • Fiscal Relations • Taxation • Cultural Heritage • Environmental Management • Parks and Protected areas • Dispute Resolution • Eligibility and Enrolment • Implementation • Ratification

A few areas worth highlighting include the following.

Recognition of Inherent Rights

At the core of our negotiations is the affirmation of our inherent rights and title, which we have never ceded or surrendered. We seek formal recognition of these rights to ensure they are protected now and for generations to come.

Education

We want to shape an education system that reflects our history, language, and culture, while giving our children the best opportunities for success. Self-government will allow us to design programs rooted in Secwépemc values, ensuring that learning builds both identity and opportunity.

Child Welfare

Our children are at the heart of our future. By reclaiming authority over child and family services, we can ensure that decisions are made in the best interest of our children, grounded in our cultural practices and community values.

Justice for Historical Injustices

Negotiations must address the harms caused by colonization, residential schools, and the ongoing impacts of the Indian Act. By acknowledging and addressing these injustices, we create space for truth, healing, and reconciliation.

Jurisdiction over Resources

We seek greater authority over the lands and resources that sustain us — particularly forests and fish, which have always been central to our culture and survival. By managing resources responsibly, we can ensure their protection, create economic opportunities, and pass on a healthy land and water base to future generations.

Last updated: January 21, 2026

Developing and adopting a Constitution for the Williams Lake First Nations holds a profound purpose and importance for our community. It should be both a political and cultural document that reaffirms our sovereignty over our territory and people, strengthens our governance, confirms and protects our identity. A Constitution determines who we are and provides us with the ability to rebuild our nation. It outlines the structure and authority of government, limits leaders’ power, and protects individual rights and values. A constitution is a documented set of rules that ensures stability and clarity, even during leadership changes, and gives legitimacy to the government. For a self-governing community, a constitution is essential as it defines the powers of the government, guides its actions, reflects community values, and prevents conflicts by establishing clear rules. It also holds leaders accountable and provides a legal framework to ensure power is exercised responsibly and aligns with the people’s values and interests. Through our own constitution, we can reclaim our authority, reinstate our laws and jurisdiction, and govern ourselves according to our traditions and aspirations. It should be a living expression of who we are and what our roles and responsibilities should be, and re-establishes our place as Secwépemc. A Ctkwenme7iple7ten, or Constitution should:

- Establish a formal structure for self-government based on Secwépemc laws, traditions, and values, rather than the colonial framework we are presently governed under,

- Provide the legal and political foundation for our Nation to exercise sovereignty over our land, people, and resources,

- Embed Secwépemc language, customs, and practices into our governance system,

- Unify our community through enhanced engagement and connecting leadership, staff and members to provide a collective vision and direction,

- Affirm cultural identity and ensures that future generations are guided by Secwépemc principles,

- Help overcome the divisions imposed by the Indian Act and colonial administration,

- Outline how we will govern ourselves based on the direction of the membership to including leadership selection, dispute resolution, and law-making processes,

- Ensure accountability, transparency, and legitimacy rooted in traditional governance models,

- Provide a constitutional basis for asserting jurisdiction over our Stewardship Area (territory) and natural resources, and

- Support legal recognition, co-management of related to rights, title, and stewardship over our traditional territory.

Developing our own Ctkwenme7iple7ten, or Constitution:

- Allows us to break away from the Indian Act,

- Moves us away from federal control and restore our autonomy,

- Replaces externally imposed systems with Secwepemc-led frameworks,

- Strengthens our position and relationships with the provincial and federal governments,

- Provides us with a legal tool to assert jurisdiction and title,

- Creates a system for future generations to inherit a functioning, culturally grounded governance system,

- Ensures continuity of the Secwépemc identity,

- Clearly outlines the rights and responsibilities of Secwépemc citizens, ensuring fair treatment and collective accountability and ways of being and decision-making,

- Protects traditional roles, land-use practices, and community structures,

- Lays the groundwork for building institutions such as courts, education systems, and governing councils based on Secwepemc values, and

- Encourages economic development aligned with our values and priorities.

The importance of Secwépemc laws (Stsq’ey) in treaty negotiations cannot be overstated. They represent the cultural, historical, and legal identity of the Secwépemc Nation and provide a pathway towards a more just and equitable future or our people. Secwépemc laws play a crucial role in treaty negotiations for several reasons:

Cultural and Historical Significance

Secwépemc laws are deeply rooted in the cultural and historical context of the Secwépemc (Shuswap) people. These laws reflect the traditional governance structures, values, and practices that have guided Secwépemc society for generations.

Recognition of Indigenous Rights

Secwépemc laws underscore the inherent rights and sovereignty of the Secwépemc people over their traditional lands and resources. These laws provide a framework for understanding the relationship between the Secwépemc Nation, their lands, and people. It also will establish the relationship between us and the government.

Self-Determination and Governance

By acknowledging Secwépemc laws in negotiations, there is a recognition of the right to self-determination and self-governance. This includes the ability of the Secwépemc people to make decisions about its own affairs, including land use, resource management, and cultural preservation.

Legal Recognition

Recognizing Secwépemc laws in Self-government negotiations contributes to legal standing, which acknowledges the coexistence of multiple legal systems within a single jurisdiction. By reconciling Secwépemc laws with Canadian laws, there is an opportunity to create a more inclusive and equitable legal framework.

Conservation of Traditional Knowledge

Secwépemc laws embody traditional knowledge about the land, environment, and natural resources. By incorporating Secwépemc laws into treaty negotiations, there is an opportunity to promote the conservation and sustainable management of these resources for future generations.

Reconciliation and Nation-to-Nation Relationship

Acknowledging and respecting Secwépemc laws in Self-government negotiations is an essential step towards reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. It establishes a foundation for a nation-to-nation relationship based on mutual respect, cooperation, and understanding.

It is the intent of WLFN’s Self-government team, with the input of WLFN Members, to incorporate our laws and principles into the development of a Self-government Agreement. We have begun research and have already began meeting with WLFN’s Elders and other NStQ Members to get input to identify Secwépemc Laws and how we might incorporate then in a Self-government Agreement.

Secwépemc laws and governance have long guided the stewardship of Secwepemcúl̓ecw through principles of respect, responsibility, reciprocity, and accountability. Rooted in the understanding that the land (tmícw) is a living being with its own spirit and rights, Secwépemc law defines a relationship of interconnectedness rather than ownership. People, land, water, plants, and animals are all relatives, and each family and community carries responsibilities to care for specific parts of the territory. Traditional governance relied on consensus, with Elders and knowledge keepers interpreting laws to maintain balance between people and the natural world.

Land use and harvesting followed strict protocols and seasonal cycles, guided by oral teachings and ceremonies that emphasized taking only what was needed, protecting key areas, and allowing for regeneration. Enforcement was rooted in social and spiritual accountability, reflecting a deeply moral relationship with the land.

Despite the disruptions of colonization, Secwépemc communities continue to uphold and revitalize their laws through contemporary land use planning, environmental restoration, and resource management. These living laws continue to sustain the health, identity, and sovereignty of the Secwépemc people and their territory.

Range Resources

Range resources—grasslands, forests, and open areas used for grazing, gathering, hunting, and other land-based activities—have always been central to Secwépemc identity, economy, and governance. Historically, they sustained Secwépemc life by providing food, materials, and the foundation for culture and self-governance. Horses, introduced by the 1750s, further increased the importance of rangelands for mobility, trade, and livestock. These landscapes also supported game and plant species such as elk, deer, camas, and balsamroot, which remain vital today.

Range lands are deeply connected to Secwépemc laws, oral histories, and spiritual practices, guided by principles of respect, reciprocity, and sustainability. Traditionally managed through family and community stewardship, practices such as cultural burning maintained healthy ecosystems. Colonization disrupted these systems, restricting Secwépemc access to key areas through Crown land tenure and settlement.

Today, range resources remain vital to cultural revitalization, ecological restoration, and community wellbeing. They support youth reconnection with the land, local food security, and sustainable ranching, while Secwépemc knowledge continues to inform modern range management and climate resilience. Protecting and restoring these lands is essential to sustaining Secwépemc identity, self-determination, and the health of Secwepemcúl̓ecw.

Read more about Our Lands (Tmícw), and Range Resources here (available in the “Resources” section).

A self-government agreement or treaty must be approved by a ratification vote by NStQ citizens before it can be implemented. To be eligible to participate in the ratification vote, an individual must be enrolled with an NStQ community under the process set out in the Eligibility and Enrolment chapter of the treaty.

The treaty will list the ways in which an individual can be eligible to be enrolled in an NStQ community, for example, membership in the community under its pre-treaty membership rules or, for a non-member who can demonstrate an attachment to the community, NStQ ancestry, adoption by a person who is eligible to be enrolled, or acceptance into the community by custom.

Ratification under the draft agreement currently being negotiated requires more than 50% of eligible voters to cast a ballot and more than 50% of the votes cast to be in favour of accepting the agreement. Those eligible to vote will be the citizens of NStQ communities over the age of 18 on the day of the vote and enrolled with their community under the treaty process.

Other conditions that must be met include:

- All eligible voters have a reasonable opportunity to review the proposed agreement.

- An official voters list is prepared and published at least 30 days before the vote.

- The vote is conducted by a secret ballot

Once ratified by NStQ, Canada, and British Columbia, the agreement would come into force on the effective date to be determined by the parties, likely several years later.

Note: The voting age is currently set at 18 or over. Should that minimum age be lowered? Let us know if you think it is appropriate for younger WLFN citizens to vote on a final agreement. Email selfgovernment@wlfn.ca to share your opinion.

The Maa-nulth First Nations show what is possible when Nations move beyond the Indian Act and reclaim self-determination. After entering the BC Treaty process in 1994, the five Maa-nulth Nations ratified their treaty in 2009, and it came into effect on April 1, 2011. From that day forward, they were no longer “bands” governed externally, but self-governing Nations recognized as a distinct order of government within the Canadian Constitution. Their lands are held in full ownership and jurisdiction—not as reserves held by the Crown.

The treaty affirms broad rights and responsibilities, from land ownership and harvesting to cultural protections and law-making powers. While the five Nations share nuučaan̓uł language roots, each governs its own lands, programs, and services in ways that reflect its unique traditions, dialect, and history.

Maa-nulth governance is grounded in timeless values: respect for all things, the knowledge that everything is connected, and the responsibility to act with care. Language, culture, and ceremony guide how they live, govern, and pass on knowledge to future generations.

By stepping beyond the Indian Act, Maa-nulth Nations now create their own laws, govern through their own Constitutions, and define the rights and responsibilities of their citizens. Their success is a living example of self-government in action—proof that culture, language, and law can come together to build thriving, independent Nations.

Get Involved!

Aboriginal Title: A unique, collective Indigenous property right to land based on long-standing use and occupation. It includes the right to decide how the land is used, managed, and protected.

Ancestral Lands / Traditional Territory: The lands historically used, cared for, and occupied by an Indigenous nation since time immemorial. These territories form the cultural and geographic basis of rights and title.

Constitution: The highest legal framework in Canada that outlines how government works and what rights are protected, including Indigenous rights recognized in Section 35.

Crown Land: Land owned by the provincial or federal government. In many areas, this land overlaps with the ancestral territories of Indigenous peoples, where Aboriginal title may still exist.

DRIPA (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act): BC’s law requiring the provincial government to align its laws with UNDRIP and work in partnership with Indigenous peoples to advance their rights.

Indian Act: A federal law governing many aspects of life for First Nations peoples, including status, reserves, and band governance. It is widely viewed as a colonial system that limits Indigenous self-determination.

Inalienability (of Aboriginal Title): A principle that Aboriginal title land cannot be sold or transferred to private individuals or companies. It can only be ceded to the Crown through a formal agreement.

Inherent Rights: The rights Indigenous peoples hold because they existed as self-governing societies long before Canada was formed. These include cultural, political, and land-based rights.

Northern Secwepemc te Qelmucw: Northern Shuswap Tribal Council (Northern Secwepemc te Qelmucw) is negotiating with B.C. and Canada in the B.C. treaty process on behalf of its four member bands: Xatśūll First Nation, Stswēceḿc Xget’tem First Nation, Williams Lake First Nation, and Canim Lake Band.

Ratification: The process by which a treaty or agreement is officially approved by a nation’s members or by a government.

Section 35: A part of Canada’s Constitution that recognizes and affirms existing Aboriginal and treaty rights, including title and self-government.

Self-Determination: The right of Indigenous peoples to make their own decisions about their governance, lands, cultures, and future.

Self-Government Agreement: A negotiated agreement that gives an Indigenous nation legal authority to govern its own affairs, often replacing parts of the Indian Act.

Title (Indigenous Title): Often shorthand for Aboriginal title, referring to the legally recognized collective ownership of land by an Indigenous nation.

Treaty: A formal agreement between an Indigenous nation and the Crown that defines rights, land use, governance powers, and ongoing relationships.

UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples): An international declaration affirming Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, land, culture, and participation in decisions affecting them.

Underlying Crown Title: The legal concept that the Crown claims ultimate ownership of land, while Aboriginal title exists alongside it, based on Indigenous peoples’ prior occupation of the land.

Case Law Supporting Land Reconciliation in the BCTC Process

Chief William’s Letter to the Victoria Daily Colonist

Government of Canada Resources about Indigenous Self-Government

MEMORIAL SIR WILFRID LAURIER, PREMIER OF THE DOMINION OF CANADA, From the Chiefs of the Shuswap, Okanagan and Couteau Tribes of British Columbia (1910)

Our Lands (Tmícw)

Recognition and Reconciliation of Indigenous Rights Policy

Transition from the Indian Act to Self-government What it Means

Treaty and Self-Determination

Why are BC and Canada at the Negotiating Table?

Teachers are welcome to use, adapt, copy, and share these assignments free of charge for educational purposes. The activities are classroom-ready and designed to support inquiry-based learning, critical thinking, and engagement with Indigenous perspectives and primary sources. These Social Studies assignments have been developed to support classroom learning in Grades 10–12, with a focus on Indigenous–state relations, governance, law, and reconciliation in Canada. They are aligned with British Columbia’s Social Studies curriculum and are intended to complement existing course materials. Students can find all the answers within this webpage.

To obtain an answer key, please contact selfgovernment@wlfn.ca.

Invite the whole family! We want to hear your input and share all voices throughout the community. We will bring the pizza and pop, you bring your questions and thoughts about the future of WLFN. Contact us at: selfgovernment@wlfn.ca or 250.296.3507 ext. 149 to arrange an info session for your WLFN family and friends.

Reach out to the WLFN Self-Government Department directly anytime you want to offer your thoughts or have questions about self-government topics. Contact us at: selfgovernment@wlfn.ca or 250.296.3507 ext. 149