It’s Better to be Inside the Tent: from Civil Disobedience to Seats at the Table

7am, the morning of Monday, September 20, 1999, two bulldozer operators reached their worksite on the 2300 Forest Service Road only to be handed a stop-work order. The order was delivered by Williams Lake Indian Band, including Chief Nancy Sandy, who had spent the weekend building a blockade and camp on the FSR near Spokin Lake, BC. Riverside Forest Products had been issued a permit to log 19 cutblocks, ranging in size from 9.5 to 42.6 hectares, and totaling a volume of 81,000 cubic metres. This was not the first time WLIB had gone toe-to-toe over this particular forest, and it would not be the last.

In the 1980s, the aggressive logging style of the day ripped through the Enterprise area, knocking the moose population of the woodland back from 2000 to just 75. By 1999, the Spokin Lake area was the last untouched traditional moose hunting ground for WLIB members. Chief Sandy, Council, staff, Elders, and the community were prepared to defend it.

Discussions about the fate of this land had been ongoing between WLIB, the Ministry of Forests and Riverside for years leading up to the blockade. Five years prior, members of WLIB successfully stopped an earlier attempt to clearcut the area, constructing a cabin on Rideau Road. WLIB had been actively fighting for a claim over the territory since at least 1992.

In 1997, legal precedent was established in British Columbia, outlining that governments and companies are obligated to consult with First Nations regarding any development or resource extraction occurring on their traditional territory. The precedent stemmed from the Supreme Court of Canada Decision Delgamuukw v. British Columbia. It is contingent on a First Nation being able to prove that the land in question had traditionally been used and is currently used by its people. In 1994, WLIB spent a huge amount of resources (which were quite limited compared to those of WLFN today) to conduct a Traditional Use Study. The study concluded that the Nation had historically used and continues to use the lands surrounding Spokin Lake for sustenance hunting, berry picking, gathering medicinal plants, and spiritual needs.

With the law on their side in 1997, Chief Nancy Sandy demanded of District Manager Jim Sutherland that the Ministry of Forests conduct a proper study on the moose habitat in the Spokin Lake area before issuing a permit to Riverside. Sutherland tried to reassure Chief Sandy by offering a “three-month literature review,” which didn’t come close to satisfying WLIB. WLIB had concerns about many factors of the proposed logging activity, including the location and length of the road, the area to be logged, and the question of who would reap the economic benefits. The ministry shrugged off the demands and issued Riverside a permit.

Despite the Nation’s countless attempts at meaningful consultation and a PR campaign which brought the dispute into the local headlines, the clearcut was still scheduled to move forward. While still meeting with Elders regularly to strategize, Chief Sandy and WLIB could see they were running out of options.

Three weeks after the blockade was established and the stop-work order was delivered, Riverside and the Ministry of Forests ceded to WLIB, modifying the permit to match most of their specifications. Rather than clearcutting massive swathes of the land, only a small patch that was affected by pine beetle was to be logged. Importantly, the entrance to the road was to be moved to a different location that allowed for a much shorter path, further away from the tenuous moose habitat. Band members were offered beetle-probing contracts: a small gesture of economic inclusion in the project. Although a positive step, this was not the end of the disputes over the Spokin Lake forests.

Five years later, in 2004, Riverside Forest Products continued to push permit applications through without proper consultation of the First Nation. In one case, Riverside allowed a window of just seven days to review the impacts of 23 cut blocks, and an additional 11 days to review another 12 cut blocks near Maze and Squawk Lakes. Riverside refused to cover any consultation costs, or to accept WLIB’s claim to the territory. Despite the Delgamuukw v. British Columbia decision establishing that corporations must consult with First Nations before developing on their traditional territory, this practice was still not consistent within the culture of forestry. WLIB had been vying for a Protocol Agreement with Riverside for the joint management of Spokin Lake with little success.

Headway was made when Tolko Industries Ltd. purchased Riverside, late in 2004. With new management came a fresh outlook on collaboration with First Nations. This came as a relief to then WLIB Natural Resource Manager Chris Wycotte and Director Kristy Palmantier, who had fought to maintain negotiations with Riverside through their purchase of Lignum Ltd earlier in the year.

The 2003 Forest Revitalization Act provided leverage for WLIB when negotiating a protocol agreement with Tolko. The act took 20% of the Annual Allowable Cut (AAC) held in renewable tenures across the province (equivalent to about 8.3 million cubic metres) and reallocated it to (among other arenas) First Nations. This meant that about 8% of the AAC in the province would be managed by, or in partnership with First Nations.

In 2006, protocol agreements were at long last put in place between Tolko and WLIB. The agreement involved, for the first time, a meaningful level of WLIB land stewardship through joint planning processes, and a resource management plan for the Spokin Lake area. WLIB Natural Resources department maintained regular consultation with Elders to ensure the joint planning was conducted to the highest standard of traditional knowledge. The newly minted agreement with Tolko also opened economic opportunities through license agreements, funding for referrals, and contract opportunities for WLIB’s Borland Creek Logging.

The battles over Spokin Lake are not the only angle WLFN has worked to gain control over its traditional territory. There have been other significant victories granting power to WLFN. In October of 2015, the Forest Stewardship Plan was approved by the Ministry of Forests for the Williams Lake Community Forest, giving WLIB a managing role over 28,840 hectares of traditional territory. Williams Lake Community Forest is a 50/50 partnership between Williams Lake First Nation (WLIB at the time of signing) and the City of Williams Lake, with mandates in place to sustainably manage the land in accordance with WLFN’s protocols.

It’s likely that nothing short of a treaty will provide WLFN with full control over its entire traditional territory. Still, between the Williams Lake Community Forest, protocol agreements with virtually every major forestry company in the region, three Non-Replaceable Forest Licenses totalling 405,000 cubic metres that were negotiated with the Ministry of Forests in 2008, and myriad other avenues, the level of sway that WLFN holds in the forestry sector has grown leaps and bounds since the 1999 blockade. This wasn’t a passive process; it came from decades of hard work, grit, and tenacity. WLFN Senior Manager of Natural Resources Aaron Higginbottom indicated that it can still be extremely difficult to halt projects that have been granted cutting permits, even if WLFN can clearly identify ecological risks associated with a project. “We still have to fight tooth and nail if we want to stop a project” he says. Higginbottom paraphrases the elders when he says, “it’s still better to be inside the tent, than stuck outside without a voice in the conversation.”

Gallery

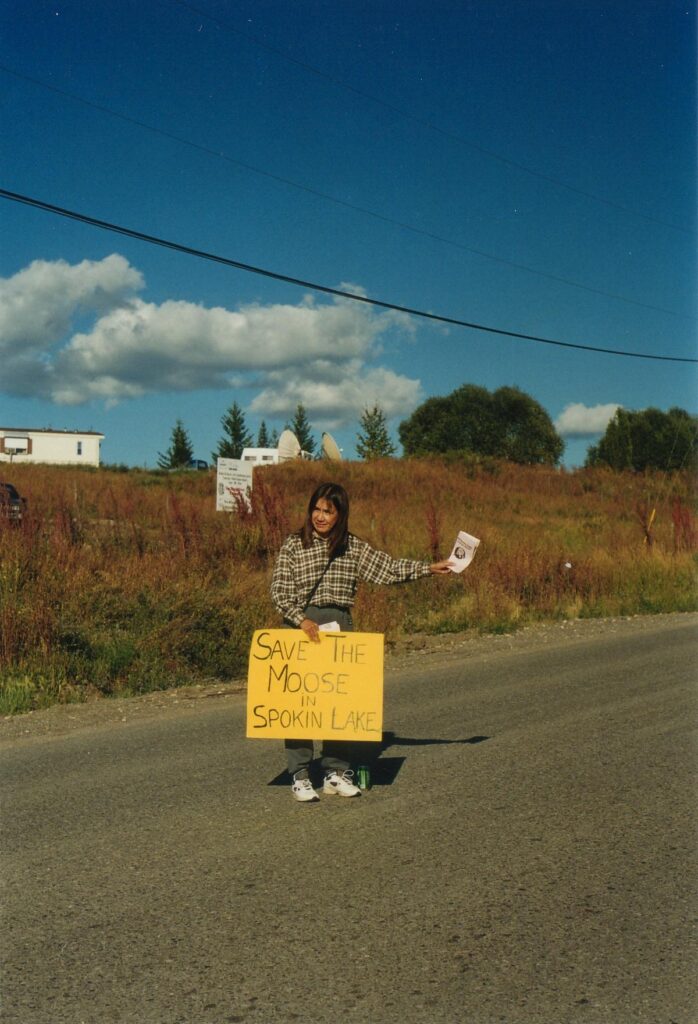

September, 1999 — Chief Nancy Sandy and Band members stage a protest to gain public attention of their battles over the Spokin Lake territory.